longtime readers will recognize this as an extension of one of my earliest Conventicles!

The town of Deerfield was first established by English settlers in the 1600s on the fertile soil of a Kwinitekw (Connecticut River) tributary, where the Pocumtuck people farmed their trinity of corn, beans, and squash, and, if the name Deerfield indicates anything, hunted for deer. The rhythm of their year was fish, berries, squash, beans, corn, deer, ice, maple. This month, which my family calls the Egg Moon, was Squannikesos, when they planted corn.

Through the Valley, in the years after Puritan settlement in the late 1600s, colonizers used brutal tactics to clear the land of its kin. Colonizers distributed blankets inoculated with measles, and introduced ecologically destructive farming practices such as the raising of pigs and the fencing of lots. Both sides burned the others’ corn and corn storehouses; this was particularly devastating for the indigenous people who had already been displaced from their seasonal rhythms. Righteous and terrified in a wide open country that was more full of sounds and creatures than any place they had ever known, the colonizers’ brutality provoked retribution.

Pocumtuck survivors resettled with neighboring tribes to the west and north, and began to participate in French raids on English settlements. In 1704, a group of French and Indigenous men attacked the town of Deerfield and killed or captured over 100 people. This is known as the “Deerfield raid.”

Those who were captured were marched across thousands of miles of winter ground to the French settlement of Montréal, where they were imprisoned and ransomed back. This practice was widespread across this region and in Maine, where settler-colonizers lived in proximity to consolidated and retreated Indigenous communities. Deerfield got many of its captured residents back, and rebuilt in the same place, and the raid became part of the town’s mythology. One of the kidnapped Deerfield residents was the ancestor of C. Alice Baker.

In 1890, writer and schoolteacher Charlotte Alice Baker (1833-1909), who went by C. Alice, he began renovating her ancestral home in the historic Deerfield Village, as a summer retreat from her home in Cambridge. She was 56. She dressed plainly and had a simple face, and late in life she looked like Mr. Potter in It’s A Wonderful Life, but in a dress, and without a scowl.

She said she began work on Frary House “to save it, to dance in it, to give her mother a home in it.”

Auntie C. lived in a world of women. In addition to her mother and her longtime collaborator Susan Minot Lane, she made the annual trip to summer in Deerfield accompanied by Emma Lewis Coleman, also a historian and a photographer, twenty years her junior. Coleman liked to take re-enactment photos; one shows a friend dressed like a Colonial matron, pulling a stubborn calf through a meadow. A portrait of Coleman herself shows her dressed as a Medieval princess, with long head scarf and flowing robes.

One day, at a luncheon with local elder women, I found myself in a conversation with a Historic Deerfield docent — Frary House is now a historic site, open only for tours. When I referred to Auntie C. as a lesbian, this woman bristled and grew agitated.

It’s not a term they would have used back then, she said. Why does her personal life matter, she said.

To me, I said, her personal life is one of the most important parts of it. Because she was choosing to live in a way that she made.

It’s true, that we don’t know who was having sex with whom, or at least, I couldn’t tell from Auntie C.’s papers. I’ve been told to look for pet names. It’s not unheard of to read romantic relationships into these women’s spaces, even by traditional-seeming house museums. The Sarah Orne Jewett House in Maine (a Historic New England property)has recently completely revised its curatorial approach to interpret Jewett’s longstanding romantic relationship with Annie Adams Fields, which includes noting the location of Fields’s portrait — next to the bed.

The 18th century was a refuge for Auntie C. and her household, whoever was sleeping with whom. Dressing in costume, conjuring a past, was a way for these women to live together, outside of the expectations of their time. That’s why the dancing matters. In costume, as J. Samaine Lockwood explores in her incredible book Archives of Desire: The Queer Historical Work of New England Regionalism (!) these women who lived without men made a place, together. Why they couldn’t dress like robots or futuristic utopians I couldn’t guess.

The Board President of the Amherst Historical Society said to me once: “I guess I have hidden in the past because it seemed simpler there.” But of course, anyone who actually thinks that, isn’t really paying attention.

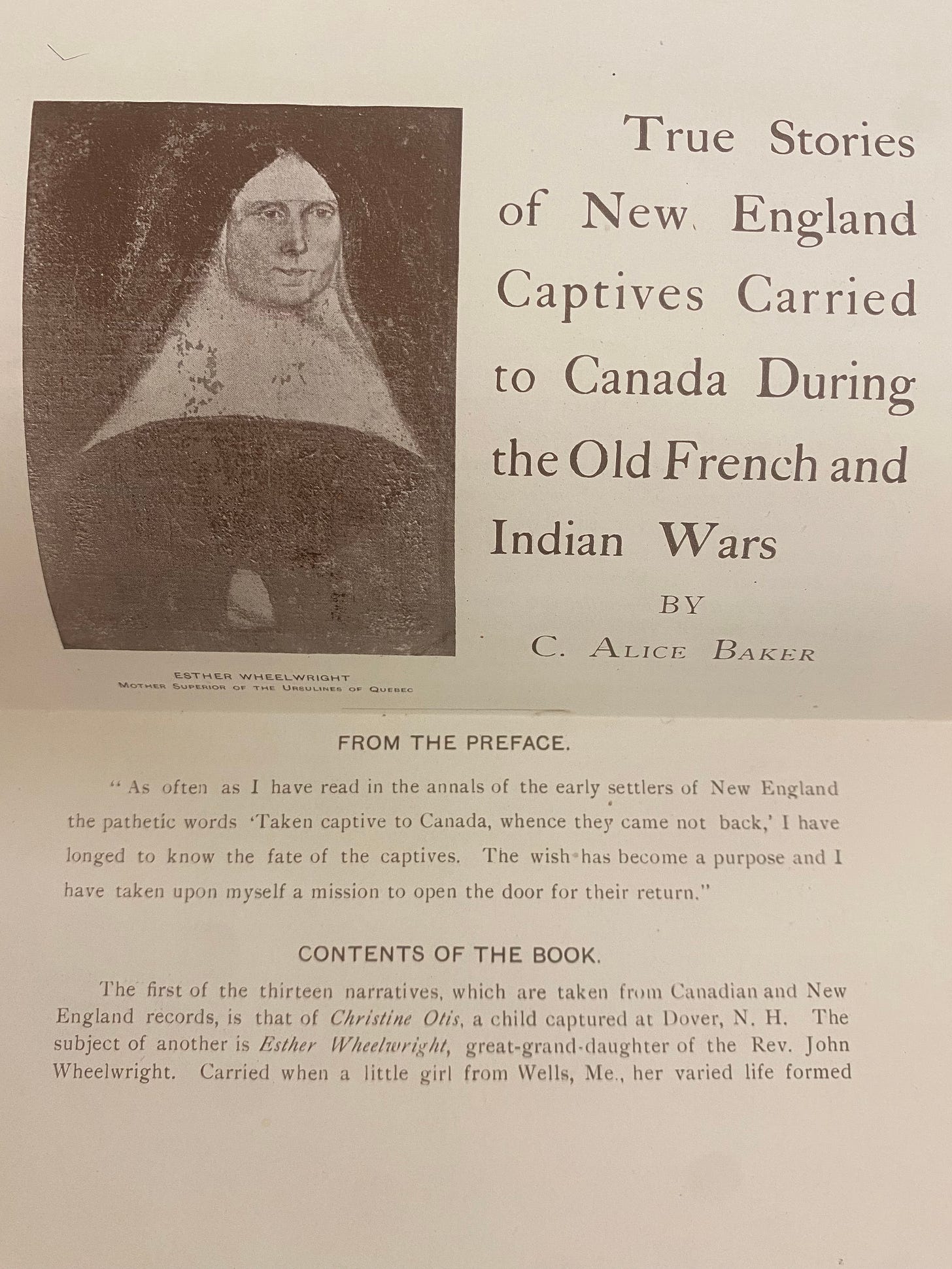

When she had completed renovations to the Frary house, Auntie C. became so smitten with the story of the Deerfield raid captives that she resolved to discover the fates of every captive who had been abducted from across the colonies, from Massachusetts to Maine. Skilled in French and Old French, Baker traveled to Montréal and across the Québécois countryside — in winter! — to chase down these stories. She published her exhaustive findings in the book True Stories of New England Captives, producing a data set used by historians to this day.

In Auntie C.’s time, it was not unusual for a woman without a PhD to write a book of history based on research practices that included both painstaking archival sleuthing and intuitive leaps into the paranormal, and be considered an expert, not a romance novelist. It was also not unusual for these women to have a mystical, genealogical connection to this history.

Reading her research logs, I got the feeling that Auntie C. also thought that somehow, by finding their stories, she could rescue the captives from the wanton cruelty of the “savage Indians.” She writes, “instinctively I hold out my arms and whisper, ‘Don’t be afraid’ to the little Elisha Searls as I see him there, in his blue checked apron and shabby homespun, just as he was snatched from his mother’s side. He stands there ready to burst into tears.” In this moment, Baker describes herself not as a historian, but as a medium, speaking with the spirit of the dead.

I can’t decide whether I find it disturbing—she, imprinting her belief in the superiority and separateness of a white race onto both the past and the future with the power she invoked as a researcher—or inspiring, with its leaps into the unseeable and unknowable.

But what I know is that to be a historian is to descend into the unknown, whether it is a world you wish to live in or not, and wait for what arises there. To become a conduit for this relationship that you establish with the past, and facilitate whatever reckoning or joy—often both!—comes from it. This is the underground of history, where things wait until we find them in the darkness.

I also think that C. Alice Baker’s search for the lost captives was a way she tried to make sense of a feeling that she couldn’t square with dancing in a beautiful old ballroom. Or maybe, a feeling that she knew lived alongside the dancing. I think she was trying to find something to do with her grief: grief at the violence beneath the surface of her fantasy, and also grief simply for the fact that the past was gone. A past that she felt ought to be hers, somehow, a past of her great grandmothers and great great grandmothers that was receding from view.

I sometimes think, I often do, really, that historic preservation is a way of trying to slow down a world that is changing faster than we can grieve what has gone, because whether the past seems ideal to you or not, and whether it does depends very much on who you are now, it can never be gone back to. In my own family, my grandmother can remember her grandmother, who was born in the 1850s. That’s nearly 200 years of memory! For C. Alice Baker, that means feeling personally connected to the early 1700s. Watching that time fade away must have been disorienting, especially since she had the sense of that time being so momentous, and of her own family’s important role in it.

“Grief is the metabolism of change,” writes Ross Gay in his book Inciting Joy, in a chapter on grief which set me to weeping on my back porch under the gentle leafless warmth of an October afternoon. “The griever knows, or comes to know, again and again,...that when that one thing changed, everything changed...The future. The past. All of it changed.” Joy and grief, dancing and burying. And changing.

The Pocumtuck dug holes in order to mark places that were important for remembering. These holes had to be maintained by regular digging; in this way it was not the hole itself, but the repetitive task of digging that caused the spot, and the story that it commemorated, to be kept in the mind of the community. I like to think of these holes as the places where they put their stories. Of course, once they were no longer able to maintain them, they filled back in with dirt and mud, the land’s constant change erasing the record of what only people wanted to remember.

During her research, Auntie C. befriended the Mother Superior of the Ursuline Convent and began a long correspondence with her. I can’t help wondering about their friendship, this unlikely relationship across faith, language and borders, between two women who lived with other women, concerned each in her own way with eternal souls.

In the 18th c, the Ursulines didn’t just take in young New England women during the period of their captivity for ransom. Some of these young women actually joined the Convent, converting to Catholicism and leaving their communities forever. One of these women — Esther Wheelwright, pictured here — even became the Mother Superior.

Puritan women had one choice: become wives and mothers. Work the homestead, stir the spitting corn porridge, defend the culture and the home against the unknown demons lurking beyond. These women worked their hands and their bodies, they did business and domestic labor, and birthed children. Lydia Maria Child imagined one way of leaving that life, in Hobomok — to fall in love with an Indian. Esther Wheelwright found another. Become a Nun.

Auntie C., Aunt Sue and Auntie Emma found another way, three hundred years later. To live together, in another kind of cloister. A cloister in time. She was still performing her spinster obligations — caring for her mother — but this became an opportunity to live in the way that she wanted, rather than a burden of care. I suspect this is why Auntie C. felt such kinship with Esther Wheelwright and her own contemporary Mother Superior.

Auntie C. also researched witch trials in the Valley. If I had forever to think about these things I would wonder why. Well, I wonder it now, but I would try to find out. Was she interested in miscarriage of justice, or Colonial violence and punishment? Had she turned her attention more explicitly to women’s issues, to women living outside traditional society?

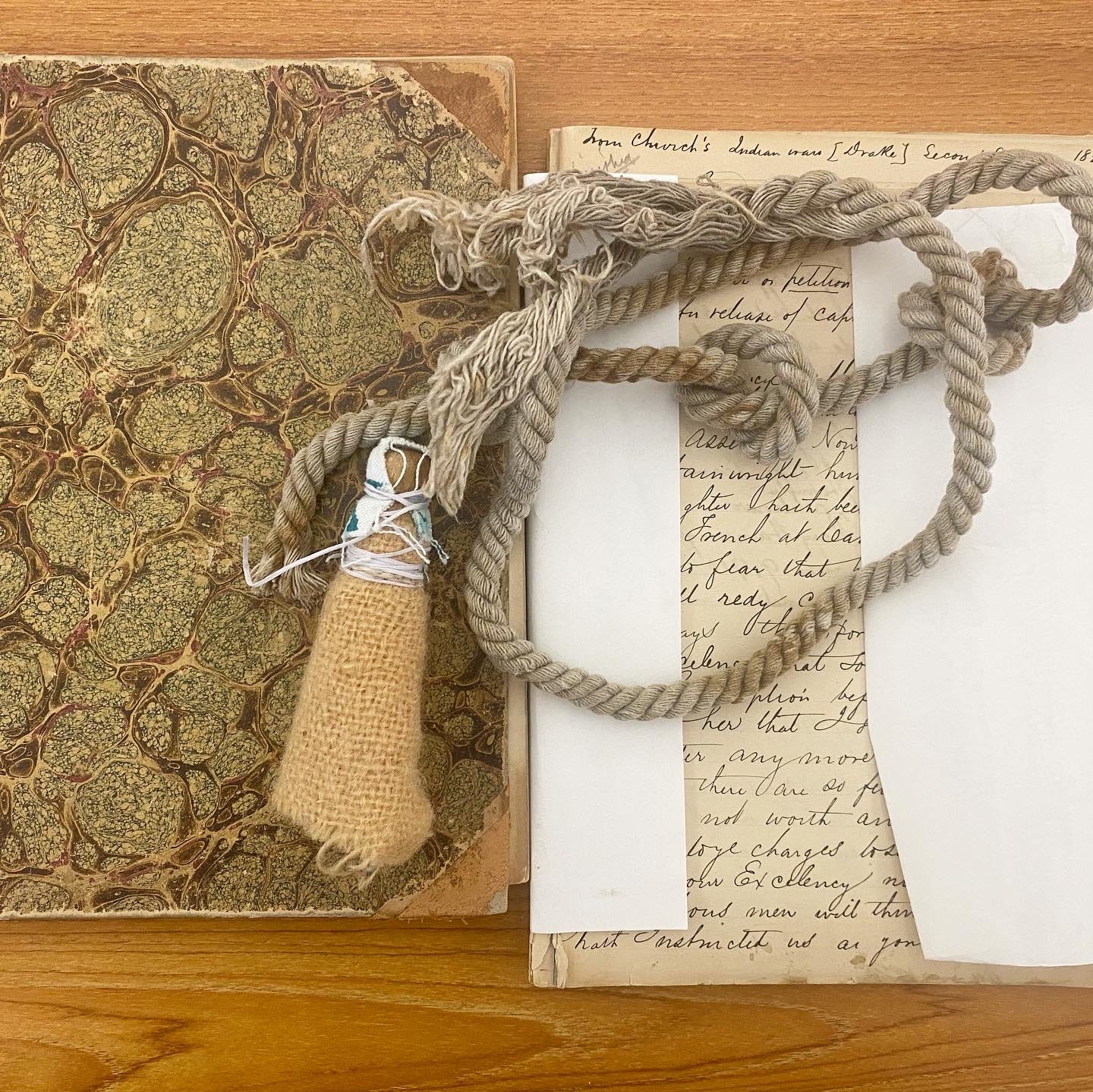

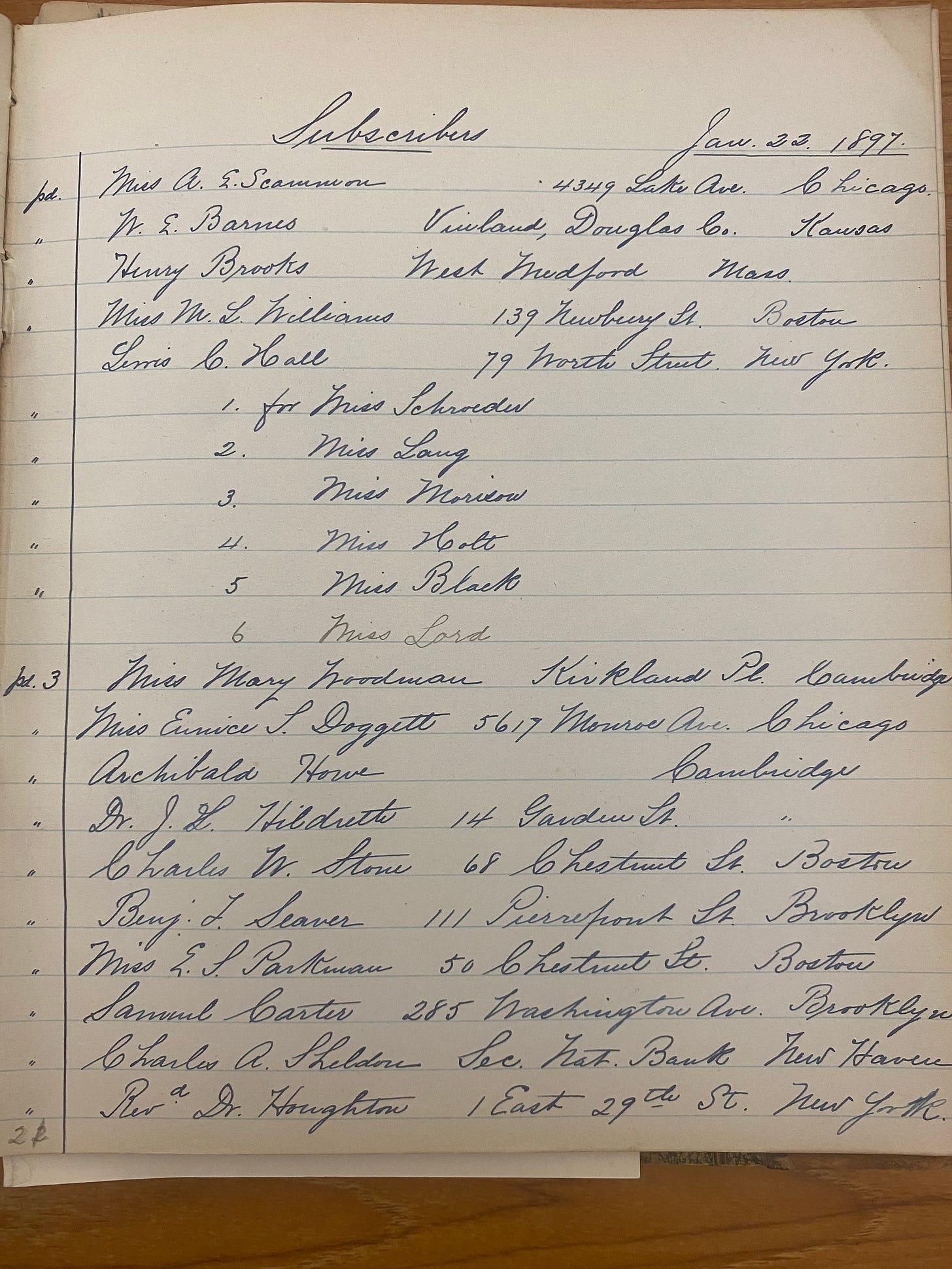

I visited Auntie C.’s papers with offerings of cornmeal, a protection potion, a poppet. While there I met another researcher, Caylin Carbonell, who I interviewed here some months later. She took subscriptions for her book, basically a 19th century Substack, very common for the time. I love seeing all of the “Miss”es — surely not all young women? This is the network of women sharing information, teaching and learning together through correspondence and summer dance party.

While I was curator at Amherst Historical, I danced in the historic house as if it were part of my job description. I made a playlist and turned up Bonnie Tyler, Billie Eilish, Whitney Houston, Beyonce and Miley Cyrus. Around 3pm, the rainbows that shone on the floor from the sun shining through the prism-cut crystals of the side-table lamp would dance with me.

That summer I would come home to my garden next to the Kwinitekw River and cook the vegetables my husband had grown, on land that was granted to settler-colonizers in the wake of the Deerfield raid, land that was first corn fields and kitchen garden and smithy, then broom corn, and then tobacco and asparagus. I began to dream of seeds, of a museum collection of things that are living, things that could be used to grow something new, something that is useful and nourishing, a museum that could make the world over and over, rather than simply collecting its detritus like an archive of doom. In my town across the river from Deerfield, a corn maze stretches from the banks of the river to the shoulders of the town cemetery, where generations of settlers lie quiet underneath silent stones. We try to find our way out of the corn, and it grows so high that we cannot see the mountains around us.

Thank you Auntie C., for showing me how to dance between the light and the dark, the past and present, and never do it alone.

I think corn might be the food that speaks to most people of America, too: “corn-fed”, for example, is practically a synonym for “all-American,” and early American cookery was distinct for its use of cornmeal, which was referred to as “Indian meal.” Corn is also the food that makes me think of grief. The burning of corn and corn fields. America, it seems to me, is a country that was born out of grief, or at least that made itself through grief. It is a place where change has been constant, and mandated, and dizzying.

For Auntie C. I made a baked “Indian Pudding,” which set somewhere between a cornbread and a custard and was supposed to be “three layered” like it always was in my childhood but never is when I make it myself. The recipe comes from the Tassajara Bread Book by Edward Espe Brown (3 c milk, 2 eggs, 1/2 c molasses, 1/4 c oil, 1 c cornmeal, 1 c wheat flour, 1/4 c wheat germ, 2 tsp baking soda, salt, baked in a 9x9 at 350 for about 45 min), which is about as far away from 19th century Colonial Revival New England as you can get, but with molasses in place of honey the flavor is all woodstove and spring ephemerals, clapboards and carriageways. Auntie C. gave a talk about the raid at a community picnic once, describing the intricacies of milling logistics in Deerfield in that period — I think flour was something she knew about. I wonder if they ate a pudding like this at that gathering, or if they served it during their costume parties, as a menu for settler dress-up. I dressed mine up with yogurt and aged lilac honey, which somehow tastes like flowers and the underside of deep springtime leaf-litter all at once.

Thank you for this "But what I know is that to be a historian is to descend into the unknown, whether it is a world you wish to live in or not, and wait for what arises there." I've been in 1700 North Andover this week with my ancestors, and it's truly the perfect paragraph for some unearthing of history I didn't know was a part of my bloodline. I was wondering if the name Charlotte Helen Abbott means anything to you. She wrote "the Abbott Genealogies, a compiled genealogies of the first Andover families," and I thought of you when I came across her work with my family line. Maybe we will discuss IRL sometime. There is a good recap of her work on her findagrave page: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/124657578/charlotte_helen-abbott