is this what matriarchy looks like?

MOTHER ANN LEE (Feb 29, 1736) and MELUSINA FAY PEIRCE (Feb 24, 1836)

The Shakers began as a tiny sect, a conventicle, really, a subset of the Quakers in early 18th century England. Ann Lee, an illiterate textile worker, had visions that she believed came from God while jailed for her membership. When she was released, she declared herself Mother Ann, the second coming of Christ. In 1772, at 36, she had another vision. She saw a tree that beckoned her and her eight followers to the New World, to America. They eventually traveled to Albany, New York, and from there to other points nearby. Harvard, Massachusetts was one of the first.

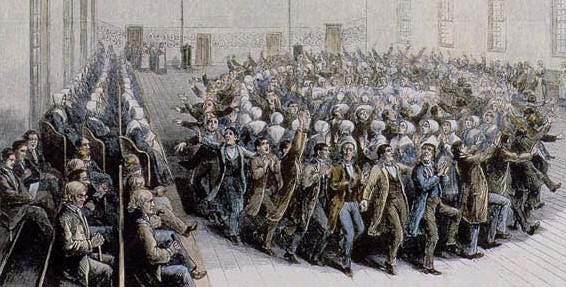

In Harvard they founded a community of brethren. They ate from an apple tree. They grew and dried herbs, made their famous Shaker rosewater, saved seeds for sale, and lived in communal celibacy. In the Meetinghouse they gathered for large Sunday meetings, dancing circularly in single-sex rings, stomping and holding their hands out at a right angle to their waists, “receiving” the gifts of God. For a brief time, they held these meetings outdoors, on a nearby hilltop (“Holy Hill of Zion”) which is now a brief clearing ringed by trees in the otherwise forest.

In The Shaker Cookbook by Caroline Piercy, from 1953, the greatest number of recipe entries for a single fruit or vegetable is for apple. Maybe that is the kind of tree Mother Ann saw in her vision. Trees were frequent visions in Shaker gift drawings as well, artworks Sisters made for each other, in a kind of trance. The Shakers were simple, self sufficient, and rejected beauty and adornment, but they had an aesthetic that was finely honed, and they sure ate well. Dried apple cake, cider cake, apple dulcet (a drink), apple dumplings, apple pie and Shaker boiled apples, not to mention applesauce, which was made by boiling dried apples in rich apple syrup. Apple parings jelly was made annually from the skins and cores of all the apples leftover from drying, a project accomplished by Brothers and Sisters during an apple peeling “bee.”

Harvard’s Meetinghouse dance floor is no longer large enough for dozens of dancing brethren, because it was subdivided to make the kitchen and dining room that one expects in a single family home (previously, it was also a chicken coop). It’s the only extant Shaker meetinghouse that is not managed by a nonprofit institution. Three friends (originally four) and I have been tending it since 2020. The pipes have burst multiple times, because the house is so vast and the heating system so inadequate. Birds have moved into the vents some winters, and once as a result of a refrigerator leak I found a family of New England spotted salamanders living in a puddle in the basement. I carried them to a pond.

We bought the Meetinghouse because we had been working and talking and dreaming about the Shakers, their utopian, millenarian vision, their seeds, textiles, drawings and bold colors, their gender equality. When the Meetinghouse came on the real estate market, we decided to share in its care, and try to build something there. What, we weren’t sure. We were all moms. Only one of us lived nearby. But in the suspension of reality that was late-lockdown, the dream of having a place where we could be together, and not confined to our homes and our families, our dishes and our children and our laundry and our Zoom screens, was irresistible.

The orchard at the Meetinghouse is about twenty years old, though some trees were added more recently. Its dozen-or-so trees are each a different, heirloom variety, and they had not been pruned in years, when we began caring for it, which suggests to me that the previous owner was more interested in “having” apple trees than in caring for an orchard. These trees now produce very little fruit, and erratically. Fruit trees are a lot of work. Two neighbors, who volunteer at a community orchard that donates its apples to food banks every fall, came once to teach us how to prune. The trees were so overgrown that their branches were reaching into each others’ space, and there was little room between branches to allow for leaf and fruit. Branches pointing upwards should be removed; major limbs that compete with the central trunk for structural dominance should be removed; all the tiny little suckers should be removed. It’s pruning season now, but four years later we don’t have an apple tending corps like we dreamed of, and I can’t figure out how to make the time for a trip out there to wake the trees up. We put the house to bed for the winter season, now, for the sake of the pipes and our sanity. The pandemic is over, and so is the open-ended possibility that crisis creates.

There is one fruit in the orchard that has surpassed our expectations, though, and also does not demand our care: pawpaws. Unlike apples, which are commonly grown on hilltops, pawpaws like damp bottomed ground. In wet months, our boots suck through the Meetinghouse’s lower garden, and the air smells of mint. In past years, the whole neighborhood has flooded so deeply that our neighbors remember navigating the streets by kayak. Pawpaws grow in clusters of two to four mango-shaped green fruits, underneath a dense canopy of broad, flat, lightweight leaves: you have to step in to a pawpaw tree in order to harvest its fruit.

The Meetinghouse pawpaws were planted in 2003, which showed abundant foresight. Pawpaws were an it fruit this year; I read so many articles about them and how they will thrive in a climate changed Northeast. But because they take so long to mature, New Englanders still don’t have many opportunities to taste them. This year, ours were ripe in mid-October. They have to soften on the tree and then fall to the ground, though they ripen okay on a countertop if they’re already full-sized. They are best when eaten truly mushy. They have large, smooth, hard skinned dark brown seeds like flat chestnuts, which are surrounded by a membranous “placenta.” Pawpaw flesh can be yellow or white, and we have one tree of each. They taste, to me, more like persimmon than any other fruit, because there is no note of acidity and the mouthfeel is smooth, soft and wet. Others compare them to mangoes (I think probably because of how they look, and maybe because of their texture) and banana (which is closer). This year, we had no community gathering, no pawpaw party, but my husband and I collected more than sixty pounds of them, and spent a feverish week delivering them to any friends and restaurants we thought might want them. (want seeds? I have some!!!)

There’s a lot you could read about the Shakers, about how celibacy isn’t a great recruitment method, how easy they are to idealize for their (now) intoxicatingly simple furniture and interior design, and, well, their bonnets. You can read about Mother Ann and think about middle-aged women having visions, what her leadership meant, what the different eras of Shaker thought connote. What I want to tell you is that Mother Ann is dead, and Shakers almost are entirely, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t matter that they tried, for two hundred years, to live as heaven on Earth, with their apple bees and circle dances. Their women were careworn and exhausted, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t matter that they were striving towards equality between the sexes. Their endtimes didn’t come, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t matter that they made their gift drawings, receiving visions from God in community, or whatever the light inside them was that guided hand to paper. The same is true for our dreams of the Meetinghouse: it’s not the thriving clubhouse or weekly retreat I wished for five years ago, when pandemic addled city people were willing to drive an hour to socialize outdoors under a canopy of apple blossoms, and I just wanted to spend time in person with friends. I couldn’t predict what this life would be like, in the After. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t matter. We’re still making art there.

Harvard has a way of feeling like a place for dreams. It has a way of seeming like it floats apart from time. Mother Ann herself was an island, described by one Sister as “withdrawn from the things of time.” The Meetinghouse isn’t really out of time, though maybe it felt like the promise of a reprieve from the onslaught of life, when we first envisioned it. Even there, the climate is changing, the elder neighbors are aging and dying. Maybe it takes a place like that to make you even try to bring a dream into the world. Pawpaws aren’t in the Shaker Cookbook, but they’re part of the Meetinghouse’s future story. Mother Ann was doing the biggest kind of long-game thinking: she made a new society. Its ruins are all over the neighborhood.

Melusina Fay Peirce, born 100 years later, identified the same necessity for women’s liberation and equality as the Shakers : cooperation. Auntie “Zina” is one of my local annsisters. Only blocks from my house, she attempted her own experiment. The Cambridge Co-operative Housekeeping Society encouraged women of different classes to pool their time and energy in doing laundry, sewing, and cooking together at a centralized location, just as the Shakers did, but without the communal living. It lasted only one year, 1870.

But “the obstacle to co-operative housekeeping,” she wrote, is HUSBANDS.

Auntie Zina envisioned that middle and wealthy class women, her peers — she came from an educated, old-name family with ties to Harvard and Radcliffe — would collaboratively fund the effort so that lower and middle class women, especially young women not yet constrained by the shackles of matrimony, could participate in the endeavor as an entrepreneurial business. Young women “have health,” she insisted, “they have strength, they have hope, they have spirit, they have vigor and elasticity and freshness of mind, they have freedom — they have everything which the faded and disappointed matron of forty too generally lacks.” Solidarity between these women and the married women was the key to her concept. Mother Ann, I guess, was a woman like this, free to imagine a different way of doing things. I, I suppose, am the other. Forty.

Women, Auntie Zina said, had not yet come to solidarity consciousness. If they did so, in places like her Society, she believed, they would be able to throw off the yoke of their oppression. She was a materialist feminist, which means that she took her analysis from Socialism: women, like other workers, were owed their portion of capital and control over their means of production, and that’s what a co-operative would make possible.

Auntie Zina was a sociologist: a sociologist with living experiments, a sociologist of the kind who needs her experiments in order to make a world that she is willing to live in. Like other sociologists of her day, her thinking had serious limits. It was hierarchical, for one. Not all women were equal; she was a raging nativist. I doubt she would have had an interest in my Nonni’s Nonna, for example, who immigrated to Boston from Sicily while Auntie Zina was trying to improve working conditions for women there. I don’t forgive or excuse her these harmful prejudices, but I also am not willing to let them obscure her work. Seeing her clearly helps me think about how to do better.

It goes without saying perhaps that the husbands of these middle class and wealthy women didn’t love the idea of paying for keeping houses that weren’t theirs. In other words, it hadn’t occurred to Auntie Zina that keeping women from working together was both the cause and the effect of their situation. Husbands tanked year two of the experiment, by refusing to let their wives attend meetings, by preventing the funds for dues from being released from their accounts, by belittling and, presumably, mansplaining all over the project.

And besides, she acknowledged, it was difficult for the women of the co-operative to sustain the work of both the new kind of world, of collective labor for shared value, at the same time as the old kind of world, to which they were still married. Such living-in-two-worlds would be necessary for a future in which only the collective work was possible, but who was willing to undertake the exhaustion of getting there? I guess this is true not only for housekeeping for any kind of change, personal or collective. Thinking of the decade it takes for pawpaws to mature, ten whole years from idea to fruit. Who feels they have that long, who is not a tree? Maybe that was Mother Ann’s secret, the message of the tree that she saw: go into the unknown. It will take time and you may not eat the fruit. But you will have planted a seed.

Our dream was and is to share the Meetinghouse with each other, and that means, since I am a wife and my life is structured around my nuclear family, it has been fundamentally limited. I’ve been trying to find a way to live both worlds. What would it look like, have looked like for the past four years, for me to take seriously the yearning for a place to share in that way? What would it look like to commit to being the ones who make the bridge between the old way, and a new? I think I am saying that 150 years later, I’m still not sure how to get us there, though I think I am also saying that I am certain I have been walking in that direction, with every turn of the Maypole dance and every night in the silence of an empty eighteenth century house, every artist residency and every political teach-in (many of which I have had nothing to do with, but have been proud to know are possible because of the love and care of my Meetinghouse Sisters). Auntie Zina didn’t give up on her vision for womanhood freed of drudgery. She wrote Co-Operative Housekeeping: How not to do it and how to do it, full of the lessons of her experiment.

I wonder if this is similar to what I was saying before about food, which is raised and harvested and prepared at great labor, only to be eaten in a single meal: that short term experiments are part of long-term thinking. That it’s the experiments that are the point. How will we know what we are willing to do, unless we try? We make the recipe over and over, and note in the margins what we changed and what we learned, what fell and what triumphed. Everyday, we have to eat. So every day we get to try. How will we understand what it takes to make a vision possible, unless we fail at it? By we I probably mean I.

We have had beautiful days at the Meetinghouse. One spring night, I stood in the meadow and waited for the American Woodcocks to begin their circular mating flights. At dusk they flapped up into the sky and shook themselves in a wide circle over our heads, calling with a high, shuddering sound called a “peent.” We had finished our dinner of millet and curry lentils and crunched across the March grass in the falling light, waiting for the show to start. The woodcock was so barely visible in the darkening sky that it was more felt than seen. I wondered what the Shakers, for whom mating and display were both against all rules, thought of these mating shows. They too danced in circles, hundreds of them praising and stamping for love not of another creature but for God, for all of creation. Their dancing was so powerful that the basement of the Meetinghouse is buttressed by granite pillars strong enough to hold the force of their feet.

Dancing, like food — that ephemeral joy, the thing that can’t be put down in words, that can’t be saved, the thing that feels just a little bit like a world you can wish into being.

Mother Ann Lee’s Birthday Cake

Every year, the Shakers made this cake in honor of Mother Ann. I made 1/3 of a batch, layered in between and on top with peach preserves and sprinkled with just a bit of wild rose sugar, since Shakers permitted themselves the extravagance of roses as a culinary ingredient, though with trepidation. I don’t have a peach tree in my backyard, and ones we planted at the Meetinghouse were destroyed by hungry deer a couple of years ago, so I used cherry and apple twigs. I can’t say I tasted it, but it’s pruning time anyhow.

Mother Ann’s Birthday Cake (from Piercy’s 1953 cookbook)

1 cup best butter (sweet, fresh if possible)

2 cups sugar

3 cups flour, sifted

½ cup cornstarch

3 teaspoons baking powder

1 cup milk

2 teaspoons rose water

12 egg whites, beaten

1 teaspoon salt

Cut a handful of peach twigs, which are filled with sap at this season of the year. Clip the ends and bruise them and beat the cake batter with them. This will impart a delicate peach flavor to the cake.

Pawpaw Shake

Cooked pawpaws are said to give terrible stomachaches to some people, so my favorite use for them is a simple shake: pawpaws in the blender, with plain yogurt.

Lovely writing!